When the World Met Muhammad Ali

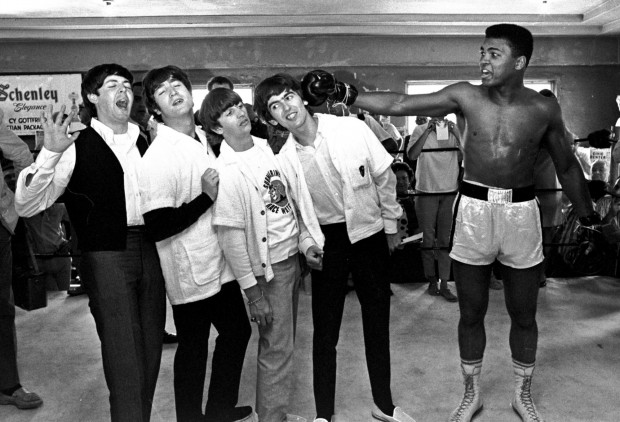

Until 1964, most professional boxing weigh-ins were boring, predictable affairs. This was not the case for Clay vs. Liston, February 25, 1964, in Miami Beach. There was nothing boring or predictable about the 22-year-old Olympic gold medalist from Louisville, KY, named Cassius Clay. Although Clay would go on to become Muhammad Ali (referred to from here forward as Ali), the world heavyweight champion and Sports Illustrated’s Sportsman of the Century, at the time, he was unknown and largely untested. In addition to Ali’s prowess in the ring, he was a natural promoter and gifted PR man. There is no greater display of his PR wizardry than the first Liston fight for the heavyweight championship.

The press and boxing fans in general heavily favored the current heavyweight champ, Sonny Liston. Liston was a seven to one favorite. Of the 46 sportswriters in the arena, 43 picked Liston to win by knockout. The New York Times’ boxing reporter Joe Nichols skipped the fight because he thought a Liston knockout was all but guaranteed.

Then the weigh-in happened.

The day before a professional fight, boxers weigh-in to confirm they are within the weight class. For heavyweights, like Ali and Liston, the weigh-in is pure formality, as there is no weight limit. Today, weigh-ins are an opportunity for fighters to talk trash, hype the bout, and intimidate each other. In 1964, it was simply a box to check. Ali changed that.

“You’re scared, chump!”

"Someone is going to die at ringside tonight!”

“I’m the champ! Tell Sonny I’m here.”

Ali soared into the weigh-in. He yelled and jumped, sang and recited poetry. He lunged at Liston and threatened to whoop him right then. His entourage had to restrain him. Journalist Mort Sharnik thought Ali was having a seizure. Robert Lipsyte of The New York Times described “an enormous amount of movement and noise exploding in a densely packed room.”

Ali acting out at the weigh-in earned him a $2,500 fine. Journalists flocked to their typewriters labeling him everything from insane to terrified. Was Ali insane? Was he scared? The physician of the Miami Boxing Commission thought so. He said Ali was “emotionally unbalanced, scared to death, and liable to crack up before he enters the ring.” His blood pressure told a similar story. At the weigh-in, it registered 200/100. His pulse was 120.

The Commission ruled that if his blood pressure and heart rate didn’t come down, the fight would be canceled. An hour later, both returned to normal. The whole weigh-in—the yelling, the lunges, his manic nature—it was all a show. It was a stunt.

After the fight, when Liston threw in the towel in the eighth round. After Ali became the heavyweight champion of the world at 22. And after Ali shocked the world, he said, “Liston’s not afraid of me, but he’s afraid of a nut.”

Ali influenced the press and manipulated Liston to create a competitive advantage.

Ali built a narrative, he created an experience, and he backed it all up in the ring (as great a talker as he was, he was also one hell of a fighter).

As marketers, narrative is what we do. When we hire at Nebo, more than anything, we’re looking for storytellers. What’s your story? How can you make it compelling?

On paper, Ali’s story didn’t look good. There wasn’t much to intimidate Liston or convince the press he was a contender. Ali was relatively untested and he’d struggled in fights against weak opponents. Liston on the other hand was so dominant that boxing writers said he was damaging the sport because he couldn’t be beaten. Liston was an ex-con. Ali was middle class. Not to mention, at the time, black athletes were expected not to make a lot of noise.

Ali rejected all of this. Ali created a narrative where he was the greatest. Liston was old, slow, and scared. Ali was insane. In part, because of the narrative Ali created, Liston came into the fight unnerved, overweight, and underprepared.

The weigh-in for the 1964 heavyweight championship was an experience. Ali created an experience for Liston and an experience for the press. He knew how to play to the needs and emotions of both. The press needed a story. He created one for them. But creating an experience doesn’t have to be brash and chaotic. Smart marketers know how to create experiences that will get people buzzing and get attention from the press.

Nebo has also stepped into the ring of creating promotional experiences. At a recent South by Southwest Festival, Nebo created positive buzz by throwing a lantern parade through the tech village. We were in town representing Choose ATL, a city-wide initiative to promote Atlanta as a tech hub and city of choice for young professionals. The lantern parade is actually an Atlanta tradition, so it was a fitting choice to get the conference buzzing about Choose ATL.

The parade got people talking. Instead of launching a press release to try to change Atlanta’s narrative, we were able to create an authentic experience to get the word out.

Ali was so apt at creating an experience, his blood pressure and pulse even got in on the act.

But it’s not all about show. Ali could actually back up the hype. As people in the industry are fond of saying, it’s not a marketing problem, it’s a product problem. Marketing is worthless without a worthy product. Ali’s intimidation, narrative, and weigh-in stunts were not going to beat Liston on their own. Ali had to beat Liston in the ring. Similarly, no one is going to move to Atlanta because they saw a lantern parade at SXSW. The product has to back it up.

The point of this post is not to say, be Ali. He’s the greatest of all time for a reason and we respect that. But if you’re going to strive for something, his legacy isn’t a bad one to shoot for.

Comments

Add A Comment