Luck of the Advertiser: The Long, Sordid History of Selling Irishness

If you’re like most Americans, you’ll probably spend Friday night wearing shamrock-shaped sunglasses, getting plastered on green Miller Lite and doing your best impression of the Lucky Charms leprechaun. I’m all for a good party (trust me, I’m Irish), but is this really the best we can do to honor a culture that has given us so much?

It’s hard to list all the things that are wrong with this 2017 McDonald’s ad, but let’s start with the Scottish tam o'shanter and faux bagpipes, the English Stonehenge and the stereotypical ginger beard. For those of you who have never been to Ireland, this is the equivalent of a Japanese McDonald’s ad featuring the Great Wall of China.

As you may have guessed, this blatant cultural appropriation is a bit personal for me. I’m 100 percent Irish on my mother’s side — tracing my roots from Donegal in the North, Cork to the South and Galway to the West.

For a country smaller than the state of Indiana and a population numbering just over six million, Ireland has had an outsized impact on the world. In America alone, nearly 35 million people claim Irish ancestry, and there is perhaps no other ethnicity on earth whose diaspora so far outnumbers the population within its homeland.

To understand this great migration and the rise of St. Patrick’s Day in America, you have to go back in time. Not all the way back to St. Patrick himself (who was neither Irish nor a snake charmer), but to the last 800 years, when the Irish were colonized early and often by their English neighbors.

The Troubles

Starting in the 1500s, Ireland’s Celtic, clan-based society was uprooted by an English ruling class who turned those famous “40 shades of green” into a agricultural grab-bag for British appetites.

As you can imagine, the Irish didn’t take this very well. To quell rebellion and keep their crappy power structure alive, the English passed a series of laws designed to subjugate Ireland’s native, Roman-Catholic population. Native Irish were forbidden from running for office, seeking foreign education, possessing firearms, buying land and building churches out of anything other than wood.

No, the Irish didn’t love potatoes for their own sake. They lived on them because they grew like weeds in the rich, rainswept soil, and they were the only thing hardy enough to sustain families condemned to sharecrop small plots of land. When the potato blight hit in 1845, things went to hell real fast.

While Ireland produced record amounts of food for the British exportation, native Irish died by the thousands. In the span of a decade, Ireland lost nearly 25 percent of its population — a million died and a million more emigrated to greener pastures like the USA. The Great Famine was a preventable catastrophe — a genocide no one talks about.

The Great Migration & Early Advertising

When the Irish streamed into New York and Boston Harbor just before the Civil War, their starvation, poverty and strange religion gave rise to stereotypes that still exist today — in popular culture and even advertising.

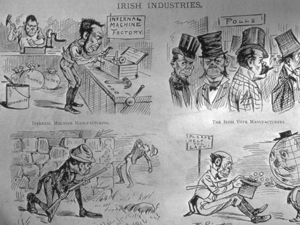

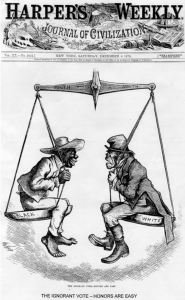

The Irish were seen as dirty, ignorant, profligate, prolific and even criminal. Depicted in advertisements and political propaganda with oversized jaws, simian features and spritely, leprechaun-like statures, the prevailing stereotypes that still afflict the Irish today were formed in that crucible of nativist hatred.

In this magazine cover, Irish and Black Americans are lampooned as the bane of the North and South.

Even today, the Irish are often portrayed as diminutive and sneaky, with squashed Rumpelstiltskin features and Hobbit-like sensibilities — a la Luckie of Lucky Charms fame.

Or they are depicted as loutish brutes with unsavory appetites, a knack for fighting and an irrepressible urge to drink their lives away. It’s no secret that the Irish are feisty — just ask this guy, or read up on the valor of the Civil War-era Irish Brigade. After all, you don’t survive famine, poverty and a millennia of colonial rule without being a little bit tough.

When the English robbed them of their native Gaelic tongue, did the Irish give up? Hell no. In the span of a few centuries, the Irish learned the language of their oppressors and gave them Wilde, Beckett, Yeats and Joyce — some of the greatest writers the English language has ever known.

Borne of great suffering, Irish culture and the diaspora that spread it around the globe is responsible for numerous contributions to music, literature, history, business and politics. So how did a culture this complex and accomplished get diluted into a bacchanal of green beer and sidewalk puking? Fast forward to those post-war boom times.

The Birth of St. Paddy’s Day

In Ireland, St. Patrick’s Day was always a sober, religious holiday, but fresh from the horrors of World War II, assimilated and self-actualized Irish Americans were basking in the glow of the world’s newest superpower and looking to celebrate their roots instead of hiding from them. Marketers seized this opportunity and, like Valentine’s Day, repackaged the religious holiday into a full-blown celebration of Irish pride and heritage.

Like any event or holiday that becomes divorced from its original meaning, eventually only sound, fury and Santa Con exist. After a few decades, St. Patrick’s Day advertising became a stand-in for Ireland itself — a green country full of people with curly red hair, freckles, funny accents and lots and lots of drinking.

In America, Irish advertising and Irish culture have become so intertwined that it’s hard to determine whether the holiday exists to sell Shamrock Shakes, or whether Shamrock Shakes exist to sell the holiday. This blend of culture and capitalism is so pervasive that my first impressions of my ancestral homeland were largely formed by Irish Spring commercials.

This commercial is packed with Irish stereotypes: beefy fighters named Brian, leather hobbit vests, leprechaun music and a fair-haired maiden with a fake accent.

Fueled by paper-thin stereotypes, St. Paddy’s Day gained popularity during the post-war boom, to the point where the watered-down holiday became an excuse for all of America (Irish and otherwise) to hit the streets and get stumbling drunk. Meanwhile for marketers, it became an excuse to use cultural appropriation to sell green shit — lots and lots of green shit.

Green beer and McShamrock debacles aside, it’s my hope that in this new millennium, depictions of Irish culture in America have reached a tipping point where our view of Celtic pride isn’t fueled by stereotypes of raving drunks or jolly, mischievous elves.

This recent Jameson commercial feels like a novel take on the “most interesting man in the world” shtick, infusing the characters in the story with some Irish wit and grit.

This ad, produced by a brewing company in Denmark, pokes fun at Irish stereotypes and ends with a takedown of cultural imperialism when the characters start speaking Gaelic.

Fueled by ads created by Irish companies, we are seeing more diverse portraits and celebrations of what it means to be Celtic — with all the humor, wit, complexity and grace of the people themselves.

Many of these ads feature real, run-of-the-mill Irish landscapes and people, and thankfully, none of the one-dimensional romanticism of American ads.

A New Era of Irish Culture

I’ve been all over Ireland and it really is as beautiful as those cheesy Irish Spring ads. The people are warm, witty, irrepressible and filled with a poetic sensibility that comes from having seen everything and still having a lot to say.

For too long the Irish have been a stereotype — a reliable joke. We are one of the few ethnicities whose ridicule eludes the boundaries of political correctness. Perhaps our good humor is the reason why we haven’t spoken up for ourselves earlier, but maybe we should start now.

The story of the Irish in America is a tale often told when immigrants flee intolerable situations — one that begins with ridicule and derision and ends in acceptance and eventual triumph.

The Irish have given us so much: Guinness and Jameson, Notre Dame and the Kennedy’s, Stephen Colbert and Jimmy Fallon, Michael Fassbender and Liam Neeson, U2 and The Pogues, Yeats and Joyce, Celtic and country music. They built our bridges and railroads, formed our first police force, gave their lives on 9/11 and shaped our great American cities.

As you may have guessed, I’m pretty proud to be Irish. And this St. Paddy’s Day I’ll be raising a glass to my ancestors — the O’Boyles, the Donovans, the Wynnes and all my Celtic brethren here in America and back home on the mainland.

This St. Paddy’s Day, I invite you to celebrate Irish history and culture in its infinite complexity. Instead of getting fall-down drunk to the The Chainsmokers, why not pour a glass of good Irish whiskey, crack open a copy of “Finnegan’s Wake” and scream out a sentence from that beautifully strange book that perfectly describes the Irish: “They lived and laughed and loved and left.”

Comments

Add A CommentI heartily agree with the misappropriation of Irish culture, even though I do enjoy the variation of musical groups that are associated with Irish culture and films that stereotype Irish figures like Darby O'Gill and the Little People. I also love films about real Irish culture, as well, of course. I just don't know many of them. I'm also proud to be Irish. I have to say that although there is a lot of of the stereotypical bar crush on St. Patrick's Day, when I was in Charleston, SC for the holiday this year, they also had a very culturally rich celebration. The day started with a mass at St. Patrick's Cathedral and then there was a parade including any possible Irish-related society from the city, including a historical society and many traditional Irish dance companies. I thought it was refreshing to see.

"

"

I do not agree http://www.beveragemedia.com/2016/11/23/trendspotting-hot-get-hotter/

Sincerely, Vonnie